Implications of the reintroduction of the Credit Card Competition Act

Overview

The Credit Card Competition Act (CCCA) has been recently reintroduced in 2023 (after first being introduced in 2022), and targets Visa and Mastercard with the aim to break up their virtual duopoly, constituting approximately 80% market share. Discover and Amex are left out.

The bill, introduced by Senators Dick Durbin (D-IL), Roger Marshall (R-KS), Peter Welch (D-VT), and J.D. Vance (R-OH), signals bipartisan support and could dramatically change both the credit card landscape, and the attractive credit card reward programs consumers have grown to expect.

In short, the bill proposes to introduce more competition into the credit card payment processing market, by requiring large financial institutions to work with at least two unaffiliated payment networks. This aims to reduce the dominance of Visa and Mastercard and put competitive pressure on the fees merchants pay for accepting card payments.

This legislation has led to a lot of politicking, with advocates for and against on both sides. It’s also led to confusion from consumers and media, with some speculating that it will drastically reduce rewards programs like points, cashback, and travel miles, while others have claimed that it could spell the doom of credit cards altogether. The reality is more nuanced.

Explanation

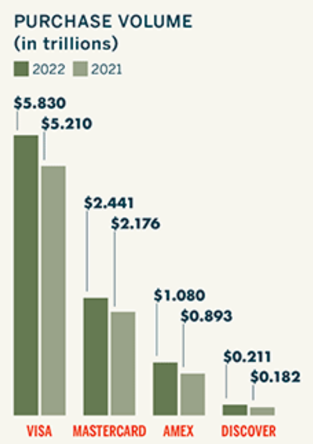

The CCCA is designed to address the significant market power held by Visa and Mastercard, which operate a near-duopoly on credit card networks. These companies provide the infrastructure that connects all banks and enables card payments to function smoothly.

Payment Network Market Share by Purchase Volume (United States)

According to the bill,

- The largest credit card issuing financial institutions in the country (with assets over $100 billion) would be required to enable at least two payment networks to be used on their credit cards, not just one.

- At least one of the two networks has to be a network other than Visa or Mastercard.

In other words, the largest financial institutions would be suddenly mandated to require two payment networks now instead of one for each credit card they issue, where one network can be Visa or Mastercard, but not both. For example, a bank issuing a Visa Infinite card would have to add another network (likely either Discover or Amex), as Mastercard would not be permitted.

From there merchants can choose which network to use to process transactions, ostensibly forcing downward pricing pressure on interchange fees due to competition.

Commentary

When first introducing the bill in 2022, Senator J.D. Vance previously conflated the impact of inflation, shrinkflation, spiking oil prices due to the Russia-Ukraine war, and several other factors on rising consumer goods prices with the interchange fees charged by payment networks.

However, it must be noted that these fees are pass-through fees negotiated between the credit card issuer and the payment network, and depending on the credit card network tier (think Visa Infinite vs. World Elite, etc.) - not a direct cause of consumer price increases.

The increasing competition amongst card issuers has led to a stampede into ever more alluring rewards programs for points, cashback, and miles. Naturally, this dramatic increase in benefits for consumers has led to a corresponding increase in interchange fees behind the scenes, as new card offerings gravitate towards higher network tiers to cover costs.

However, surprisingly, this has not led to a corresponding increase in payment network revenue. Visa, Mastercard, and other payment networks actually earn their cut from a lesser-known network fee, which is typically around 0.14%. This is the fee merchants pay for the privilege of using their networks. This fee alone constitutes the billions that Visa and Mastercard earn annually. The other 1 - 3% interchange fee actually goes directly to the financial institution that issued the credit card to the consumer.

Therefore, targeting these interchange fees may not entirely be a bad thing, but it actually misses the key point that payment networks are not the actual beneficiaries of these higher fees. Their primary metric is credit card purchase volume, which has increased dramatically in recent years and Americans continue to increase their credit card usage.

Naturally, those with the most to lose (the banks) have raised concerns about the potential for consumers to lose out on rewards programs.

However, the reality is that interchange fees; the fees that card issuers receive when you tap your phone or card on a purchase, only constitute 5 - 25% of the income that card issuers derive from credit cards.

The real money is made on annual fees, interest income, late fees, cash advances, and balance transfer fees. Statistics vary by bank but on a $180 ARPU, interchange fees may only comprise $20.

The heftiest card issuer income source is from interest – the imposing 25% APR peeking out from the fine print. Therefore, rewards are effectively subsidized by interest income from Americans burdened by high-interest credit card balances. Individuals who miss payments or do not fully understand that they need to pay their balance in full each month are effectively subsidizing the rewards enjoyed by the top 20% of cardholders.

The bigger question is thus not whether interchange fees move a few basis points downwards, but rather whether reliance on these additional fees is a sustainable strategy for the future.

As for smaller financial institutions, the impact would likely be minimal. It’s unclear if this will have an impact on financial technology startups either, as their sponsor banks generally fall below the $100bn asset threshold, and Visa/Mastercard could stratify their offerings to maintain similar fees in the face of downward pricing pressure.

“The vast majority of banks and credit unions in the country—all but the biggest 30 or so—would not be subject to the bill’s requirement to add a second credit card network.” - Short Summary of the CCCA, Office of Senator Dick Durbin (D-IL)

Conclusions

The jury is still out on whether the CCCA is a net-negative. Regulation is often like catching a falling knife. It’s a crucial aspect of safeguarding consumers and ensuring fair markets, but can often have unintended effects. Putting controls into place hurts, regardless of whether they pan out positively or not. The other challenge regulation faces is that while the benefits are clearly visible, the negative effects, or tradeoffs, may remain largely invisible.

With the recent appointment of J.D. Vance as Trump’s Vice President ahead of elections in November 2024, it raises questions about the mid- to long-term prospects of this bill. This legislation could serve as a wake-up call to financial institutions, which have long competed on functional aspects of banking, to move towards more cognitive and emotional values in their products and services.

Many credit card issuers have warned that this could spell disaster for the considerable credit card rewards, benefits, and programs consumers have come to expect. However, this may be no more than scaremongering as rewards are unlikely to suffer dramatically (keyword - dramatically). However, it could also lead to a more competitive market with potentially lower costs for merchants and consumers.

By potentially reducing the dominance of Visa and Mastercard, yes, the CCCA could foster a more competitive landscape in the payment processing industry. The real question is where will the new realized economic value go? If merchants suddenly save 1% on every credit card transaction, enabling them to top up their margins, are they more likely to pass savings to consumers rather than a credit card issuer making another 1% on interchange fees?

Looking at the positive competition in card rewards programs, and the recent track record of retailers divorcing prices from costs and pocketing record profits post-COVID, I’d put forth the hypothesis that surprisingly, we may be better off with the banks. Financial institutions, while still critically short on goodwill post 2008, face competitive pressure to pass benefits to consumers in the form of credit card rewards. Retailers can really just do whatever the hell they want.